That is no country for old men. The young

In one another's arms, birds in the trees

- Those dying generations - at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

Form and content work productively against each other in the first stanza of ‘Sailing to Byzantium’, one of the great Irish emigration poems. Yeats is telling us that he must abandon the perishable domain of human love, sexuality; death and reproduction for some more enduring kingdom, one less carnal and fugitive. Yet even though the opening demonstrative already places this perishable domain at arm’s length (‘That’ rather than ‘This’), the imagery which portrays it is tender and mutedily sensuous. And this grants the natural, human world of the dying generations a grace and preciousness which makes it hard to abandon. Yeats is refusing to make things easy for himself by setting up a convenient straw target of the fleshly world he is leaving behind. Instead, he pays homage to what he is repudiating. He does this, too, by rather courteously suggesting that the fault is his own and not that of the dying generations — that the place is unfit for ‘old men’ like himself, a self-deprecatory phrase which one can imagine costing this youth-obsessed poet a fair amount of amour propre. We suspect that he believes that the profane realm of the dying generations is pretty degenerate anyway, but he is in elegiac mood, and thus tactful enough not to say so outright.

Instead, in a charmingly diplomatic gesture, he discreetly tucks the phrase ‘Those dying generations’ as a kind of warning aside into his otherwise alluring portrait of the young, the birds and the fish. The punctuation of the first five lines of the stanza has the effect of placing all these items on the same level. This suggests an equation between the erotic young and the birds and mackerel, which is scarcely much of a compliment to the former. Once again, then, there is a delicately muted criticism: human beings are really just as helplessly caught up in an endless biological cycle as salmon, which may be one good reason to sail off to Byzantium. Even so, Byzantium does not sound all that appealing an alternative, at least at this point in the poem. That rather too contrivedly imposing line ‘Monuments of unageing intellect’, with its plodding stresses and surplus of solemnity; is perhaps intended to sound faintly rebarbative, in order to throw a final flattering light on the sensuality being left behind. There is also, perhaps, a slightly schoolmasterish feel to the admonition ‘all neglect’, as though a spot of finger-wagging is going on here. But the poem gets away with it.

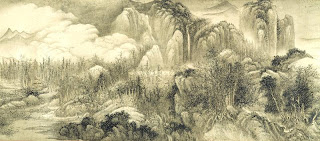

Yeats is not the kind of writer who explores nature in Keatsian or Hopkinsian detail. There is nothing lavish, profuse or sensuously detailed about the birds in the trees, the salmon-falls and the mackerel-crowded seas. ‘Fish, flesh, or fowl’ sounds more like a grocer’s terminology than a poet’s. ‘Mackerel-crowded’ is a fine stroke, and ‘mackerel’ (if the pun may be forgiven) a splendidly mouth-filling word; but ‘the young in one another’s arms’ and ‘birds in the trees’ are deliberately bare and notational. It is as though Yeats is just touching them in on his poetic canvas, without the least intent to lend them complex, convincing life. They are little more than emblems, like (for the most part) the swan in ‘Coole Park and Ballylee’.

Yet the poem’s achievement is to create the effect of lavishness and profuseness from these few meagre, economical items, an effect which would have taken Gerard Manley Hopkins at least another dozen lines. The stanza generates a cornucopian sense of abundance out of the sparsest of materials. And whereas one feels that Hopkins might have been carried away by this potentially inexhaustible fertility, Yeats remains rigorously in control, as the orderly syntax suggests. By about line 4, we are growing a little anxious: what are all these bits and pieces adding up to? Then, suddenly, a main verb (‘commend’) locks authoritatively into place in the next line, to bind these various elements together and lend them some overall thrust and coherence.

It is as though the chain of brief phrases, with its rapid, cumulative buildup, generates a sense of mounting excitement, one those young lovers might find familiar. Its grammatical open-endedness suggests that this copious piling of life-form upon life-form could in principle go on forever, creating just the sense of exuberance and prodigality that the verse is after. But that clinching main verb, not to speak of the beautifully intricate rhyme scheme, is on hand to assure us that everything is under control. It is as though Yeats’s breathing-in, in preparation for the delayed arrival of the main verb, has been deep enough to allow him to voice one brief phrase after another (‘the salmon- falls, the mackerel-crowded seas. . .‘) without things getting out of hand. So the intellect is not just in Byzantium, to be encountered on disembarking, but is already unobtrusively at work in the present. The exclamatory excitement of the lines, with their staccato rhythms, hint at the possibility of an ecstatic loss of control in the face of these fleshly delights, without ever corning remotely close to it.

- Terry Eagleton

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

O sages standing in God's holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enamelling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

- William Yeats